Blog

AV’s will Save How Much Money?

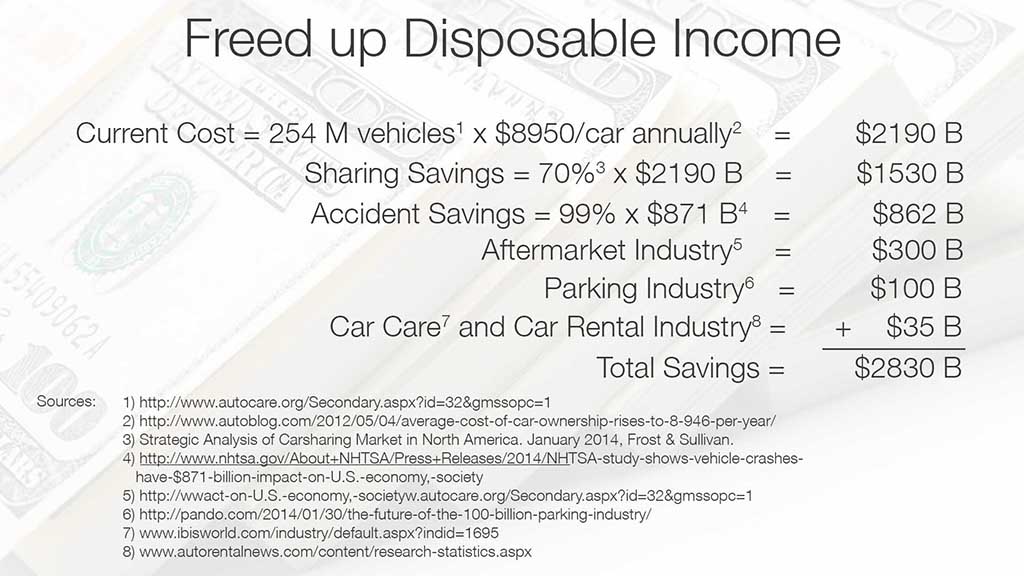

This is a chart that shows how much money autonomous vehicles may likely save Americans.

It starts with taking the 254 million cars in America1 and removing the $8950 annually that we’re all paying2 to use them privately. Then we add back in the reduced amount of money that shared car users are will be paying3 to get a baseline expense number. Next we assume that autonomous vehicles will be at least 99% safer than human driven vehicles (Google’s fleet is already proving safer than that) and adjust for the $871 billion we’re currently paying for accidents in America.4 Finally we take out just a few of the major industries that rely on private car ownership like the aftermarket,5 parking,6 car care7 and car rental8 industries that Americans are currently paying for.

And that’s just the hard costs. If we also put a value on the 75 billion hours America spends behind the wheel9 every year, and I’ll value that time at the US national average wage of $42,70010 and we assume a 2000 hour work year then that means that time is worth 1.6 trillion dollars.

So the total savings from autonomous vehicles come to about $4.43 trillion dollars. Every twelve months.

AV’s Causing Unemployment?

Will there be unemployment resulting from the advent of autonomous vehicles? In the short term, you betcha. Here’s a list of just some of the major professions I see being impacted by the widespread adoption of autonomous vehicles.

Here are links to all those numbers.

Bus Drivers = 654K drivers in 20121

Taxi Drivers = 233K drivers in 20122

Delivery Truck drivers = 1270 K drivers in 20123

Long haul truckers = 1700K drivers in 20124

Material moving operators = 651K drivers in 20125

Construction equipment operators = 410k drivers in 20126

Retail motor vehicle and parts dealers = 1880k jobs in Feb ‘157

Automotive repair and maintenance = 883K jobs in Feb ‘158

This is obviously a disaster to all the people working in these professions and their families that should not me minimized. But keep in mind this transition is going to happen over the course of several decades, so there’s time for people to retire, train for new careers and figure out that these are the “buggy whip” professions of the 2020’s and 2030’s. I am deeply empathetic to the economic hardship this structural change in our economy will cause these industries, but suggesting in 2015 that autonomous vehicle technology is a net evil because it will put eight million people out of work is like saying in 1990 that the internet is a bad thing because it will put all the postmen in the unemployment line. The internet grew our economy more than perhaps anything since the industrial revolution or WWII industrialization and it created industries we couldn’t have even imagined in 1990. It wasn’t that hard to postulate Amazon or Craigslist, but could anyone have imagined Match.com? Or chat rooms? MMPOGs? Bitcoin? Doggles? LuckyWishBone? This is fun, I could go on all day, but suffice to say, the list is very, very long of industries and the tens or hundreds of millions of jobs that the internet has created. In spite of the immediate job loss, autonomous vehicles will ultimately create a productivity revolution by freeing 75 billion hours Americans are currently spending sitting behind the wheel.9 I believe this productivity revolution will unquestionably have a net positive effect on our economy.

How Could Autonomous Tech ever get that Cheap?!?

In this website I make claims about being able to purchase autonomous fleet vehicles for $12K or $25K apiece in the coming decades, which may seem ridiculous when the most common LIDaR (Light Detecting and Ranging)1 unit used in many of the original prototype vehicles costs $75K2 alone!

It’s easy to be skeptical, but let me walk through an analysis of why those $12K or $25K price points aren’t ridiculous. First of all when I postulate a $12K autonomous vehicle, I’m talking about a Cabin Commuter rather than a full size vehicle. Also, recall that I’m talking about the mature market for autonomous vehicles twenty or more years in the future where vehicle architecture and manufacturing reflect consumer usage, which means that 75% of all vehicles being manufactured are going to be small, single person Cabin Commuters. The reality is that autonomous technology is going to decimate car sales in the industrialized world and cause the market for wheeled transportation to explode in the developing world, but that’s decades away and the extent to which it will happen is somewhat speculative so I’m going to analyze this in terms of the current automotive market for simplicity. I’m also going to use 2016 dollars for simplicity.

Enormous manufacturing economies of scale

The global automotive industry manufactures about 80 million cars per year right now, and if Cabin Commuters are 75% of that market in the future then that means we’ll be manufacturing 60 million Cabin Commuters per year. This means the industry is building around 5 million each Cabin Commuters every month spread across a dozen or more major automobile manufacturers. With that economy of scale, amazing things start to happen. Now I realize people may be more subjectively familiar with gasoline vehicle prices so let me start there. If this small Cabin Commuter platform was a combustion powered vehicle and Toyota, VW or whomever was 1) manufacturing half a million of them per year, 2) the vehicle weighed less than one thousand pounds, 3) it was legally a motorcycle so consequently not beholden to the majority of automotive regulations and 4) it was a fleet vehicle, analogous to a taxicab rather than a consumer product that was intended for sale to private customers, it’s easy to imagine that they could get the price down to around six or eight thousand dollars per unit. Right now electric vehicles are more expensive than their gas counterparts, but there should be a heavy emphasis on right now in that statement. Keep in mind the global auto industry manufactures about eighty million gasoline engines every 12 months but even if one includes hybrid vehicles, which far outsell pure electrics, electric vehicle sales are only about 700K units3 per year globally so we’re only manufacturing 700K EV battery units annually, most of which are small hybrid battery packs. Imagine a day when those ratios are reversed and we’re selling 79 million EVs and less than a million gasoline vehicles and keep the following in perspective. Right now everyone’s excited about Tesla building a Gigafactory in Nevada to manufacture enormous quantities of cost-effective batteries. That is pretty exciting, but by the time we need to manufacture 60 million Cabin Commuters per year and 79 million electric vehicles per year, there’s not going to be one Gigafactory in Nevada, there’s going to be hundreds of Terafactories all around the world. Again, the economy of scale will be overwhelming. The lesson is that the higher purchase price that electric vehicles are currently saddled with won’t last once we enter those production levels and benefit from that economy of scale.

Potential for distributed data collection

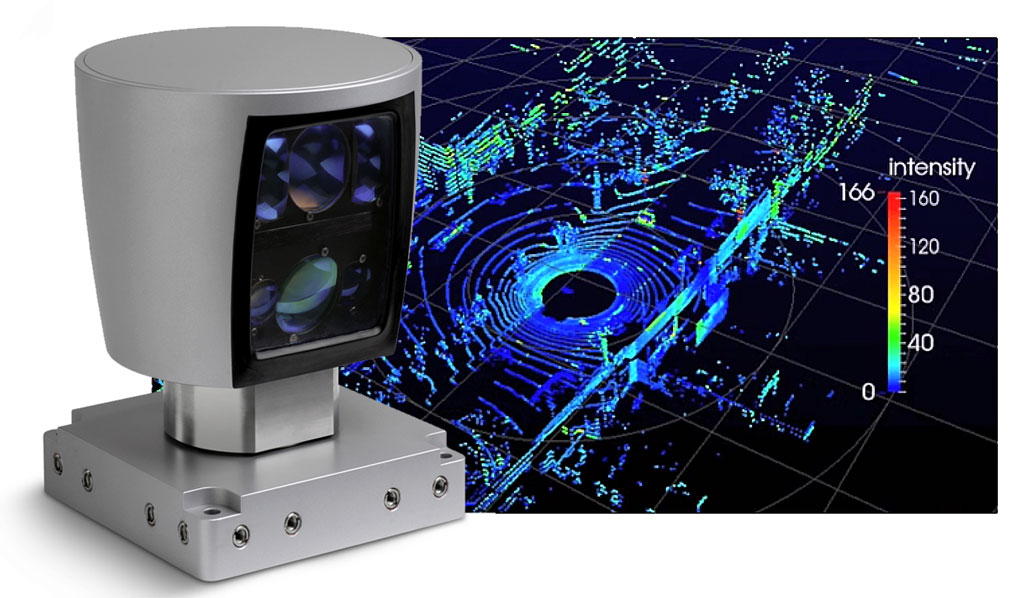

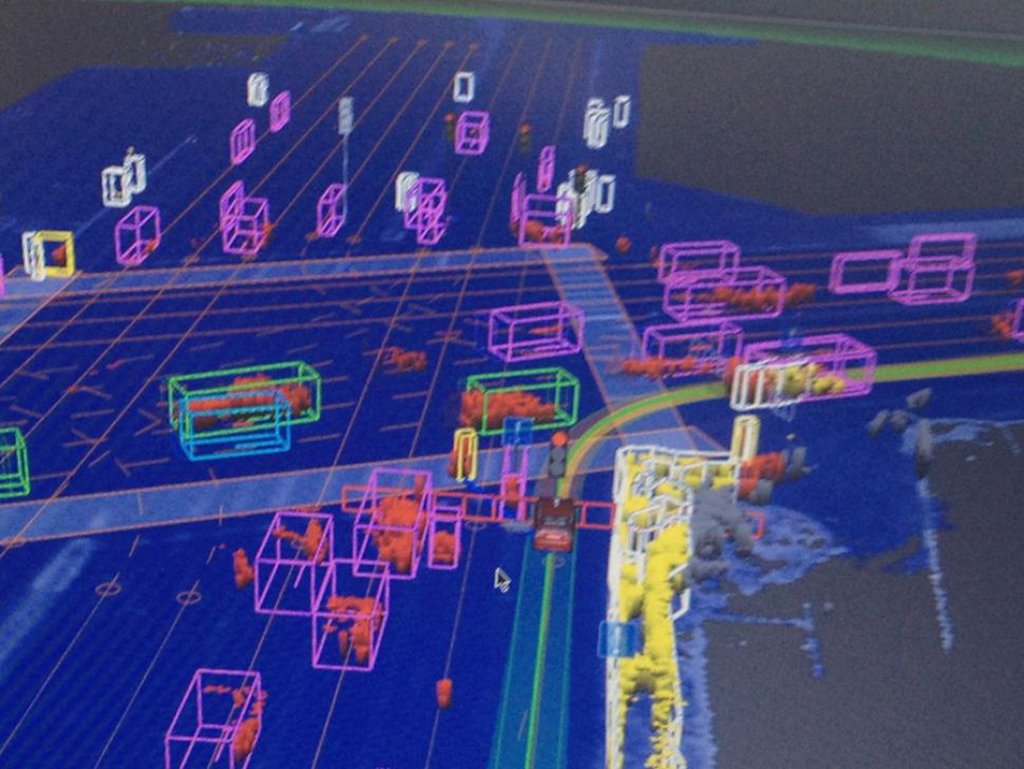

If the unit price for the automotive package of each autonomous Cabin Commuter is six to eight thousand dollars, then that means we still have 50%-33% of the budget of the entire cost of the vehicle just to pay for the autonomous tech. That’s pretty significant. Also consider this possibility. All autonomous tech basically boils down to the following: There are several pieces of hardware that emit electromagnetic radiation (radar, LIDaR, ultrasound, etc) into the environment and then read and measure the return signals. Other pieces of hardware only take electromagnetic radiation in without emitting it (video, GPS). Processing power then analyzes all those electromagnetic returns and creates a virtual map of the environment that the vehicles then use to navigate within the environment. A graphic representation of the virtual data map looks like this.

This virtual map is what the vehicles need to navigate, and the map should be universal among all the cars inhabiting that traffic ecosystem. Since they all need access to the same map, consider the possibility that in crowded environments where there are lots of cars it may not be necessary for every vehicle to be independently, redundantly observing and creating the same virtual map with its own hardware/software suite. What if the vehicles could digitally share a common virtual environmental map that was produced by only some of the vehicles? What if in the middle of a city where there are hundreds of vehicles within a hundred yard radius only every other vehicle needed to have the hardware/software capability to create the virtual map? What if it was only every fifth car? What if it was every tenth car and the rest of the vehicles could all just receive the virtual map through networking technology? What if only every twentieth vehicle required the full electronics suite? etc. It would be highly speculative to suggest what that number is right now but if only every fifth vehicle needed to have the full autonomous suite, the effect of that would be that even if the full autonomous suite never dropped below $25K, the effective per unit cost of the autonomous suite would drop to $5K per vehicle, which is really very inexpensive. All that being said, I think the autonomous suite will easily get below $25K in the coming decades. A recent study from Boston Consulting Group4 predicts that in a decade or so a full autonomous suite in a vehicle may cost perhaps $10,000 on top of the price of the vehicle itself.

Hardware optimization

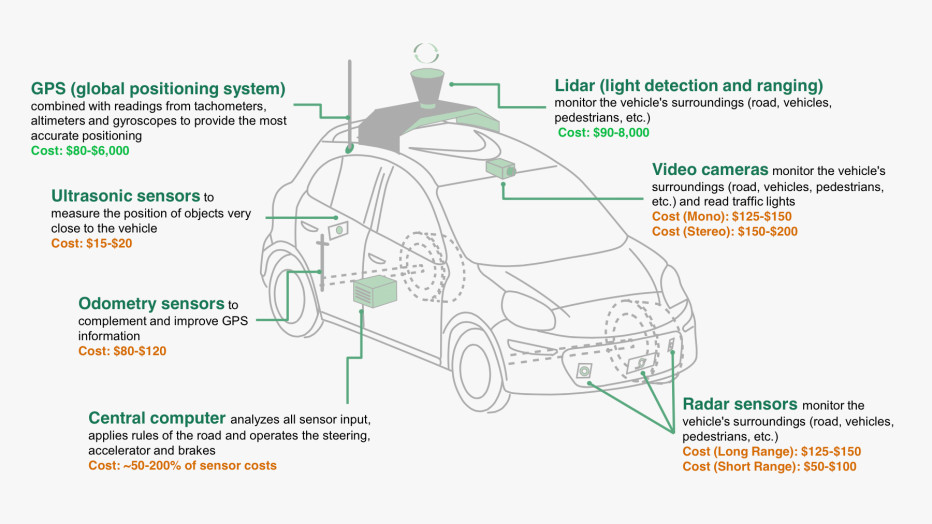

This is an infograph from a report done by Boston Consulting Group that shows the price range of the various hardware items required to control an autonomous vehicle.

Most of the hardware described is no more than tens or hundreds of dollars. The three big ticket items are 1) the LIDaR, 2) the high resolution GPS and 3) central processing power. To get a better understanding of how these price points might come down let’s look at the LIDaR hardware as an illustrative example. As mentioned above, the 64 channel unit that most of the early autonomous vehicle prototypes were using cost about $75K. That’s not much to a mining company that routinely buys $5 million dollar mining trucks by the dozen, but it’s two or three times as expensive as a sedan marketed to the middle class in America, so that price point is completely out of the question for mass produced, commercially available autonomous vehicles intended to be sold to the middle class in America. In 2014, Velodyne released a 16 channel LIDaR puck5 unit that costs about $8000, which constitutes an order of magnitude price reduction, but is still too expensive to put on a $25,000 sedan. In early 2016 Quanergy announced6 that they had developed a solid state LIDaR that could produce a million environmental data points per second that would only cost $250. the device only has a 120 degree field of view so it would likely require mounting three units on any autonomous vehicle, but regardless, $750 for three sensors is another order of magnitude decrease in the price of one of the most expensive pieces of autonomous vehicle hardware. This, folks, is how autonomous vehicle technology becomes cheap over time. To suggest the price point isn’t going to eventually plummet is to ignore the entire history of technology, Moore’s Law and the fundamental reality of exponential development and growth.

AV’s End Terrorism?!? Please…

Some people have claimed that autonomous vehicles will end terrorism. How is that possible? What do cars that drive themselves possibly have to do with geopolitical conflict? How could an autonomous vehicle make people that live ten thousand miles away lose interest in expressing violent manifestations of dissatisfaction at Western cultures?

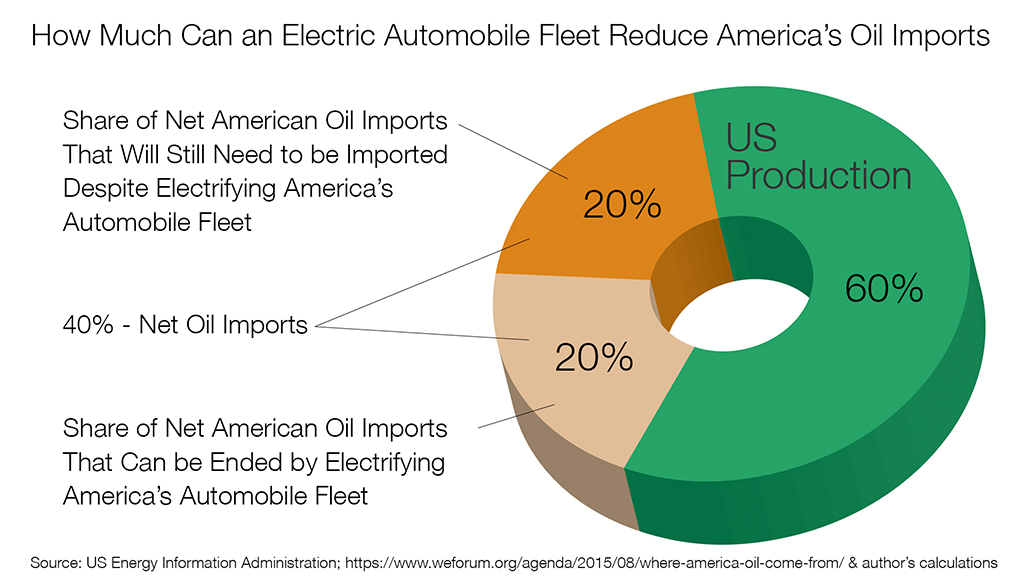

This website is dedicated to describing how the advent of autonomous vehicle technology will cause a macro societal transformation in the way that consumers all around the world use automobiles. This transformation will cause upheaval in many parts of American and global society, but the disruption most relevant to this subject is the fact that automobile usage in The Mobility Cloud heavily favors electrification of the automobile. Once it’s overwhelmingly advantageous to fleet vehicle operators in The Mobility Cloud to use electric vehicles, they will start investing in that technology almost to the complete exclusion of internal combustion vehicles. If America’s consumer transportation fleet becomes almost completely electric, that’s going to cause an enormous macroeconomic change in America’s oil importation habits. But what will that change be? Can we quantify it? Let’s find out.

America imported 7.1 billion barrels of petroleum products in 2015.1 The analysis I’m about to do is slightly muddied because America primarily imports crude oil (78% of imports)2 rather than gasoline or other refined petroleum products. America then uses its massive refining capacity to turn this crude oil into gasoline and diesel fuel and many other petroleum products. The excess refined petroleum product that we don’t consume is exported to other nations. If one balances all the imports and exports, America net imports about 40% of all the oil3 we need to meet our energy needs. Again, I’m simplifying across refined and unrefined petroleum products, but for the broad stroke of this analysis these numbers are usable. Our appetite for petroleum products is staggering and in particular, our consumption of motor fuels like gasoline and diesel is enormous. In 2015, America consumed 140 billion gallons of gasoline.4 It’s difficult to measure diesel used strictly for transportation from the supply side because diesel production is grouped together with heating oil, which is not used for transportation and a lot of diesel is used for purposes other than transportation as well. If we look at it from the demand side, though, we learn that 4% of all vehicles in America5 are diesel powered, and that 4% of vehicles is heavily biased toward larger vehicles with worse fuel efficiency than the average gasoline car. So to account for diesel consumption let’s say that diesel vehicles account for 5% of all the transportation fuel consumed in America, which, doing the math, would equal 7.4 billion gallons annually. So adding 7.4 billion gallons of diesel to 140 billion gallons of gasoline consumption means that our total transportation fuel consumption is 147 billion gallons per year.

There are 42 gallons in a barrel of oil, so this 147 billion gallons of transportation fuel required 3.5 billion barrels of crude oil to produce, which is 49% of the 7.1 billion barrels6 of crude and other petroleum products that America imported in 2015. So autonomous vehicle technology can’t end the importation of foreign oil, but it can cut it in half.

This is where autonomous cars can start to impact national energy policy and international geopolitical dynamics.

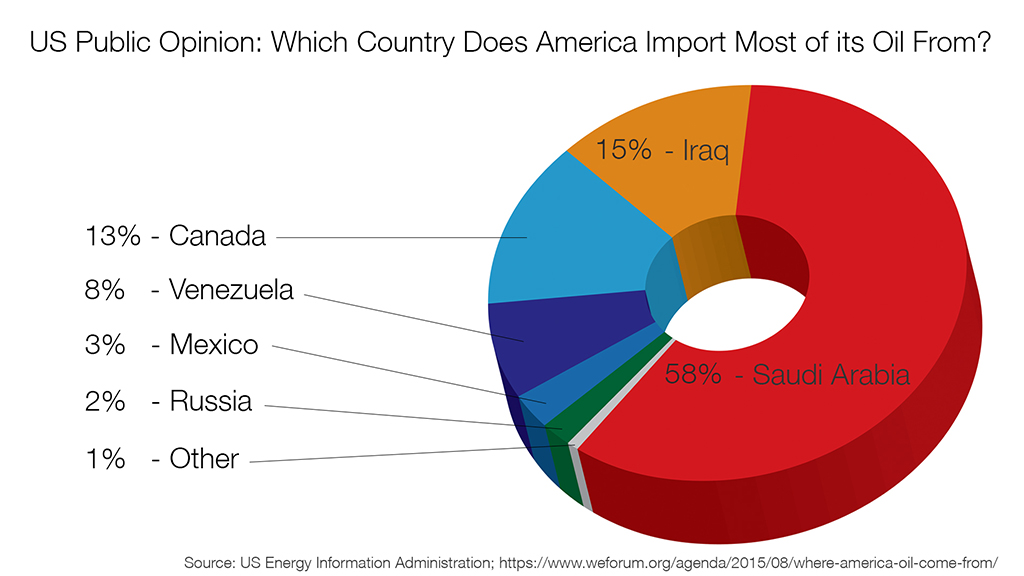

We just learned that autonomous vehicles have the potential to cut our oil imports in half. What does that mean? Does that mean America will buy half as much oil from Saudi Arabia and we’ll have half as much terrorism? Hardly. The next step in this analysis requires understanding where our oil comes from. In a poll in 2015 it was revealed that Americans think this is where we primarily source our oil.

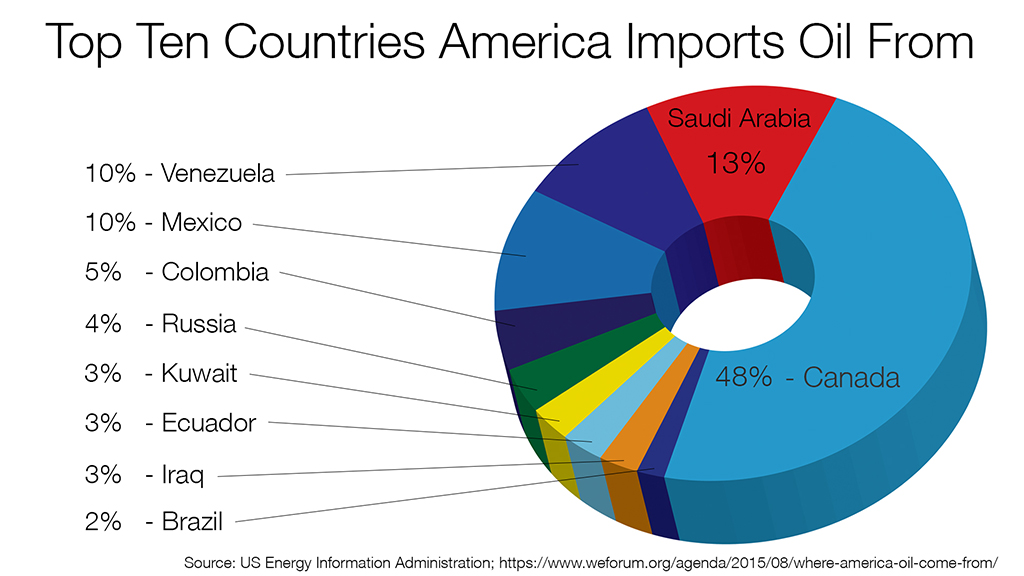

The truth is that in the first half of 2015 the top ten exporters of oil to America were the countries depicted in the pie chart below.

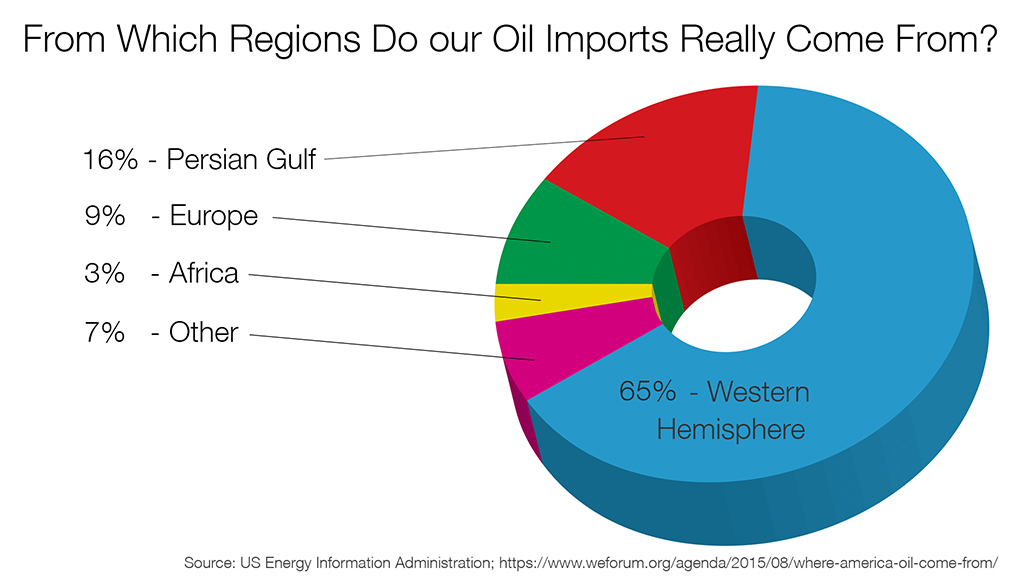

This misperception is the result of media attention that’s been given to the relationship between the global petroleum market and political instability in the Persian Gulf region, including the funding of and motivations behind terrorism. Note that Canada is overwhelmingly our major source of petroleum. Saudi Arabia is in a strong second place and while Kuwait and Iraq are both on the chart they are both further down the chart. The sort of terrorism that’s associated with the world oil economy, however, is really a problem that’s associated with the Persian Gulf region rather than one that’s tied to any individual country. Every five years it seems to be a different country that is causing America most of the problems from that region. America invaded Iraq in the early 1990’s. Iran has been a problem for decades. Osama bin Laden was from Saudi Arabia. Right now ISIS in Syria and Iraq is giving us the biggest headaches. Given this diversity, it’s more meaningful to look at this from a regional standpoint rather than a nation by nation perspective. This pie chart below shows where we imported all of our oil from by region in the first half of 2015.

This pie chart tells us that we only import 16% of our oil from the Persian Gulf region. We learned earlier that electrification of our national automobile fleet, which will be inevitable in a world of on-demand transportation, will allow us to reduce our imports by 3.5 billions barrels per year, which is almost exactly half of all imports. That means that if nothing else changed, we could stop importing oil not just from the Persian Gulf region, but from every single country outside the Western Hemisphere while simultaneously reducing our imports from North and South America by 23%, which, if we so chose, could mean that America would purchase 90-95% of our crude oil from Canada and obtain the rest from our southern neighbor, Mexico.

That’s pretty exciting. Autonomous cars could reduce our oil importation habits such that we only purchase oil from primarily Canada and secondarily Mexico. Does that mean we won’t see this guy any more?

That’s really the big question. To answer it, first of all keep in mind that this transition to a commercially owned, all-electric automobile fleet, and consequent reduction of our oil imports, will take decades, and probably more than twenty or thirty years. This is a very long game that we’re playing. Even if we give it enough time for our automobile fleet to completely electrify, that only reduces our overall national petroleum needs by about 20%, which is still an incredible improvement, but not nearly enough to get us entirely off petroleum products. We still need them.

If we’re not buying any crude oil from the Middle East, that means America can pack up its air bases in Saudi Arabia, bring the Fifth Fleet that’s currently steaming around the Persian Gulf home and stop having our soldiers traipse around the desert, right? The answer to that is, “maybe.” On one hand, even if America herself isn’t purchasing crude oil from The Persian Gulf, that region’s extraction capability still has to be available on the world market in order to stabilize and feed global oil markets. If Middle Eastern oil extraction or distribution capacity is compromised that would have a huge effect on the world petroleum market. That’s why it’s in America’s strategic interest to protect all the oil producing capacity in the Persian Gulf, even if we’re not personally customers for it. On the other hand, with America’s bloated and continually growing federal deficit, will we be willing to protect the Middle Eastern oil industry primarily so that SE Asia and China can benefit from it? Especially considering that competition from China and the Four Asian Tigers have played a large role in the decline in the American industry in the past several decades. America isn’t very excited about the prospect of ceding military control of this region to China, Russia (it would be in Russia’s strategic but not economic interest to do so), or, heaven forbid, Iran, but we’re not thrilled with a being nineteen trillion dollars in debt7 either.

Great Britain ensured access to the Middle East’s oil industry with their military from the 1700’s until World War Two, but was so reduced by the war that in the following years they closed all their bases “East of Suez.” It’s not hard to imagine that America may go through a similar rebalance of our strategic interests against our economic limitations in the coming decades, and if that happens, understand that the primary source of conflict between the Western and Muslim world will be removed.

No more importing oil from the Persian Gulf means America doesn’t have to be involved in wars in the Middle East. The end of the US military’s presence in the Middle East means the end, or at least a dramatic reduction in Middle Eastern based terrorism. No more terrorism is an enormous step toward healing the damaged global relationship between the Western and Muslim world.

Whichever way this goes, don’t let the more subtle point be lost here, though. Regardless of whether or not America chooses to end its military stewardship of the Persian Gulf, cutting our national oil importation by half and ending all oil imports from the Persian Gulf is a huge step in disentangling America from the Middle East. America and the Gulf States are still heavily enmeshed in other ways, but those cultural, commercial and other interests are largely conducted by choice. We don’t currently have the choice to stop purchasing oil from Gulf states. Autonomous vehicles very will likely change that.

But I’ll Never Give Up My Car!!!

When I present this content to automotive designers or engineers I occasionally get more or less laughed out of the room because they all say that Americans simply don’t want to drive little commuting pods. They want to drive big SUVs and alphanumerically named German vehicles. And you know what? They’re right! In the current usage paradigm, that is exactly what consumers want. Consumers don’t want to travel around in an emasculating little commuting bubble. But the problem with that objection is that it’s an extrapolation argument in an industry about to experience the greatest disruption in its history. The automotive industry isn’t taking seriously the psychological depersonalization of transportation that’s going to be an inevitable consequence of shared mobility. Allow me to offer an analogy. A hundred or more years ago we used horses for transportation and labor.

Horses were woven into the very fabric of our society and our personal psychology.

Man and horse weren’t just the team that made America; horses are a sentient species capable of returning love and being a part of a person’s life. In that context it was inconceivable to think that mobility consumers would ever choose the smelly, hard to start, cantankerous thing pictured below over their horse that they had been relying on for generations.

Tens of millions of Americans had a cultural love for their horses, and some even felt a more personal level of love for their horse, similar to what pet owners feel for their pets today.

A hundred years ago some people literally loved their horses the way people love their dogs today. Except that in this analogy the horse wasn’t just a pet, it was the family’s car, tractor and savings account all rolled into one. It was inconceivable that that society would ever give up its horses. And those feelings for the horse ran much deeper than a soccer mom’s preference for an SUV or dad being into hot rods. Those feelings, though, as strong as they were, weren’t enough to save the horse from being tossed into history’s transportation scrap bin.

To quantify this, if one takes the number of horses in 1915 vs. 19601 and then cross references that information with the U.S. historical population,2 there was one horse for every 4.6 people in America in 1915. By 1960 that number had fallen to roughly one horse per 60 people in America. That’s more than an order of magnitude decrease.

The lesson is that nothing is sacred in the realm of transportation, except people’s desire to get around. The history of change suggests that Americans’ love for big vehicles isn’t immutable, and the history of disruptive technologies suggests that our love for unnecessarily large vehicles won’t be enough to prevent a macroeconomic change in the way consumers use mobility technology, just as early Americans’ love for their horses wasn’t enough to keep the horse relevant.

To give a more succinct analogy, saying that American transportation customers will never reduce their reliance on privately owned cars is like saying that American communication customers will never reduce their reliance on telephone land lines.

The End of Car Culture

Automobile enthusiasm has been a hallmark of our society for over a century. The car is the manifestation of personal freedom in our society.

But the truth is that the world’s car culture has been diminishing for several decades now1 with most research showing that millennials and postmillennials are less emotionally involved with their cars than their generational predecessors.2 In fact, research shows that this generation is much more interested in this-

Than they are in this-

Once we no longer own cars and no longer feel emotionally attached to them that will be the final blow for automotive enthusiasm. America’s car culture has been a defining aspect of Americanism for a hundred years but it’s eventually going to become a provincial hobby for the wealthy, like horse enthusiasm is today. Owning and working on cars will become an anachronism until eventually it will be illegal to drive a human controlled car on a public road.